MOBB DEEP > Does music really kill?

By Sky High (Stress Magazine)

AL 40 October 1999

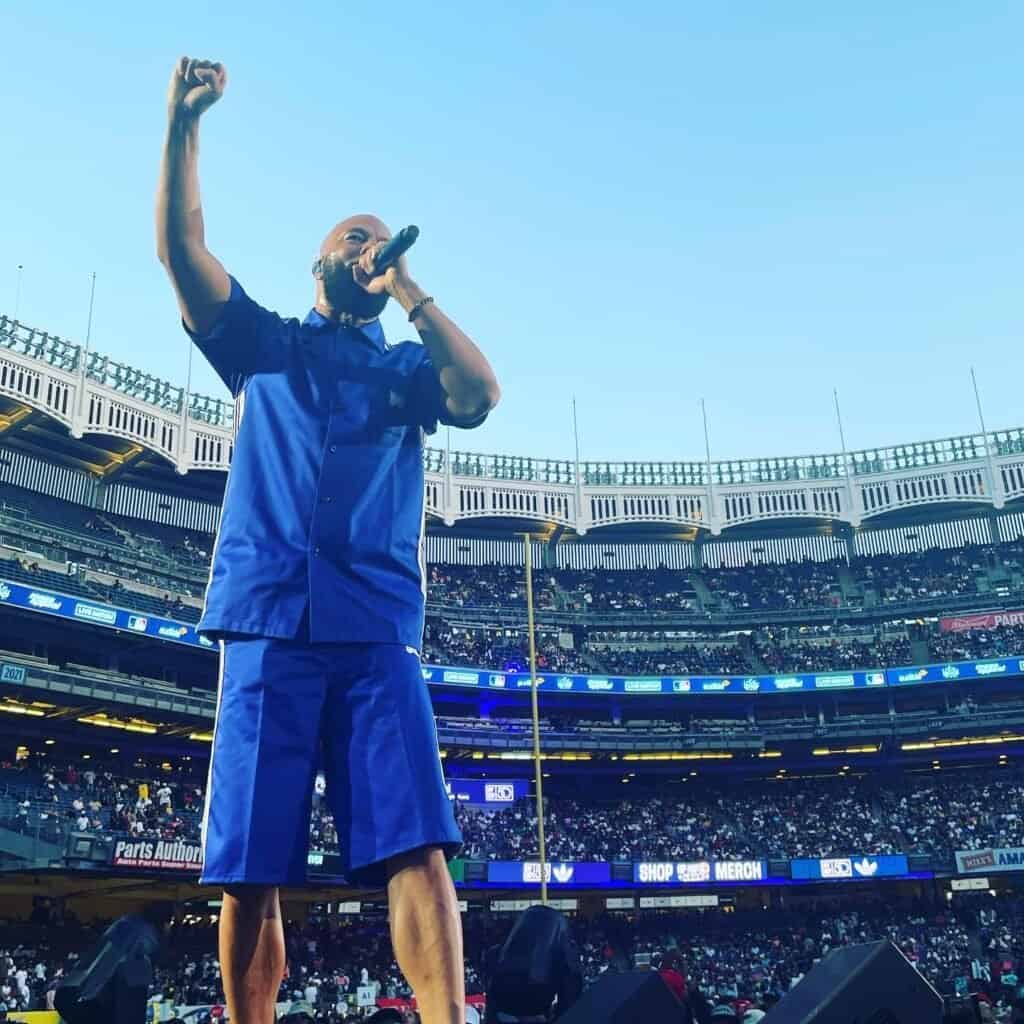

Although almost everyone recognizes them in the names Havoc and Prodigy the Mobb Deep are a crew, a ʻfamilyʼ, as they prefer to call themselves.

During all the studio recording sessions Iʼve had occasion to attend in my life, only the mc and the sound engineer were present besides me, but it works differently for Mobb Deep; while theyʼre recording it seems that the whole of Queens gathers around them.

I wondered if those dozens of people in the studio were sincerely supporting Havoc and Prodigy, or if they were simply taking advantage of the status of fame and success achieved by the Mobbs. After spending some time with QBʼs celebrities, I began to realize that Prodigy and Havoc benefit as much from their crew as the crew benefits from them. The fact that they are constantly on the move gives them the opportunity not to have to adapt to other places or environments. Over the past two weeks, I have observed them at work in the studio while shooting their film on Long Island, and the way they are allows them the flexibility to move as they please and to do what they want, despite the cold, antiseptic environments in which I have often found them. Although Prodigy and Havoc have moved away from the projects to work in the suburban setting of Long Island, their connection to the neighborhood remains unaffected by the fact that they have brought their people with them. And perhaps this is exactly how the two conflicting worlds of show business and reality, as perceived by Mobb Deep, collide, generating the particular mixture that is “Murda Muzik.” Thereʼs a proverb that says: ʻYou can take a person out of the ghetto, but you canʼt take the ghetto out of a personʼ; for Mobb Deep this expression has no value because they carry the ghetto with them, literally.

Prodigy: “Mobb Deep is a whole team, a large number of people if you ask me. The Mobb Deep includes me, Hav, Noyd, Gambino, Ty Nitty, Godfather, Mike Deloreon, Gotti and other ne*rs.”

Havoc: “We don't forget our people, we are still struggling. Our rhymes are about nothing else, no matter how much money we can make, that's not really the goal. We will always continue to write about the struggles that our people have to do because we don't want to leave them behind. There are people who are always in it to make a quick buck, selling drugs and screwing around... Having grown up with these people I feel that if I can I have to help them, because if they were in a privileged position and I was going through a difficult situation, I would want their help.”

Most recording sessions are scrupulously broken down into precise time slots during which the artist and sound engineer work on the tracks and vocals and then mix it all together. For Mobb Deep it works a little differently. For Prodigy and Havoc, recording an album means going into total hibernation; a kind of Hip Hop sabbatical away from everyday life, during which music becomes the focal point of everything, consuming their every moment of energy. They bivouac in the studio for days on end, smoking endlessly, ordering exorbitant amounts of Chinese takeout, drinking cases of beer, until they manage to get a piece worthy of inclusion on the “Murda Muzik” album. Then the process begins again. To be honest I have to say that as an outside observer the creation process comes across as terribly boring. The day I arrived they were writing lyrics for a piece whose beat had been sampled from the movie “Scarface.” It was a nice piece but, like a good meal when broken down into a week's worth of leftovers to be consumed, by the sixth hour of listening to the same loop without any variation, I was nauseated. Despite the monotony Prodigy remained focused on his notepad, scribbling rhymes relentlessly without even lifting his eyes for a moment.

Prodigy: “My grandfather played with some great bands, I heard a lot of jazz when I was growing up. He played with Miles Davis, Dizzie Gillespie, and all kinds of jazz musicians. My grandfather also influenced me a lot because I lived with him for a while and I remember him writing music. He used to sit and take notes, all day, every day, scribbling, writing songs. I used to get tired of seeing him like that, then I really didn't understand what he was doing during all that time. Now I do. I remember how demanding he was on himself, when I was a kid I saw him able to stay up whole nights to finish that stuff. If my grandfather worked nights I have to do it too, you know?”

Prodigyʼs work ethic matches his grandfatherʼs perfectly. I was getting tired of being in that studio because I was witnessing the whole process, from the metamorphosis of the song to the very atmosphere in which it is created. Bags of chips and empty boxes of chicken nuggets lay on the multitrack mixer that resembled a Star Trek console. A thick cloud of smoke was hovering over my head, and it seemed that at the same instant one joint was being turned off, another had already been rolled and turned on. From the sound engineer to his assistant, to Prodigy, to Godfather, to Noyd, to singer Chinky, the mystic weed was making a complete circle. I already felt out of tune at just touching the air, so you can imagine what happened after Ty Nitty elbowed me and invited me to join in. I know I shouldnʼt have done it, but I did. Iʼm guilty without appeal. The only problem was that I couldnʼt do the interview. Reality and fantasy had merged, pulling me into a hallucinogenic whirlwind as the pulses of the studioʼs huge woofers pounded in my ears. My eyelids began to droop like birthday balloons without helium, my words came out slurred ... I ʻwoke upʼ only later when I was in the vehicle that was transporting me to Old Westbury, Long Island.

LONG ISLAND

Behind me sat a white guy of a certain age hired by Prodigy for the film that would bear the same title as the album, “Murda Muzik.” He introduced himself to me as ʻthe supervisor in charge of weaponsʼ. According to what he said, he had loaded two dozen of a sub-type pistol and several sawed-off shotguns into a truck for one of the scenes in the video. After showing me a .40-caliber semi-auto he carried strapped under his shirt, I believed him. “Iʼve been hired for all the guns in Godzilla and Die Hard 3...“ he told me, following up the list with titles from other action films, ”...Iʼm one of only two regularly licensed ʻWeapons Coordinatorsʼ that exist in New York,“ he continued, showing me a laminated card. ”This card allows me to carry any firearm in either public or private areas at any time. I can wave a Desert Eagle rocket launcher out the window of my car.” As we exited the highway, a haze of thick smoke from rolled cigarettes began to fill the passenger compartment. Once we arrived at this secluded building, located in a forest near North Shore, I rang the doorbell, hoping that I had not triggered a complicated alarm system instead. Surveillance cameras were located at the corners of the entrance. A fat, grizzled guy with a thick Long Island Jewish accent opened the door for me. I thought I had the wrong address until he replied to wait because the crew had not yet shown up. The basement was roughly the size of four average Manhattan apartments, complete with ping-pong table, pool table, and photographs of the homeownerʼs sons riding horses (I would later find out that the back of the house had stables and a barn). During the next three and a half hours, in which I waited for Mobb Deep, I was privileged to enjoy the company of Old Westburyʼs entire teenage community. Provincial teenagers kept coming and going, taking turns asking me if indeed Eminem and Nas were also coming. Although by now I wasnʼt even sure about that, I answered the only thing I knew: Mobb Deep was the one who was supposed to be coming, no one else. Hearing this, most of the kids assumed a puzzled expression, followed by the inevitable, “And who are they?” I tried to explain it in the simplest way; ʻthe Mobb Deep are a rap group from Queens, consisting of two mcʼs, Prodigy and Havocʼ. Then I proceeded to hum as best I could a selection of songs from their repertoire (“Shook Ones,” “Survival Of The Fittest,” and so on). The confused looks turned to utter bewilderment the moment I took to explaining the slang meaning of the term ʻMobb Deepʼ. It was all to no avail, after each of my lectures the kids would repeat, “So Nas and Eminem are coming?” Although theyʼd never be able to tell the Mobb Deep from the Furious Five, there was no doubt that by the time they arrived Prodigy and Havoc would still be recognized; they would be the only blacks within miles. I immediately wondered what might have happened if they had just happened to be in that neighborhood on any other night. Needless to say, the Mobbs were noticed as one notices an ingrown toenail, and although neither Nas nor Eminem showed it, the boys attacked them anyway. To consternation on the rich landlordʼs part, the crew of more than twenty people stayed settling the building well past the agreed upon 1 a.m., extending the filming until about 6 a.m. To consternation on the part of the landlordʼs wife I plundered the refrigerator cleaning it out of meat sandwiches probably left over from a recent bar mitzvah. To consternation on the part of two black girls wearing very high heels and see-through dresses, there were some of the neighborhoodʼs white girls trying to get the attention of the Mobb Deep crew. One of the ones I had tried to ʻistractʼ just before said to me, “Oh my God, I mean, isnʼt that Mobb Deep? Wait, his name is like Prodigy, right? I canʼt believe my eyes, I mean...but isnʼt that someone else from the group or something...oh my God!!!” I didn't mean to be rude, but I stood in disbelief without answering her. I couldn't believe that chicks like the ones in Sir Mix-A-Lot's “Baby Got Back” video could really exist. The two black girls burst out laughing in unison as I tried to deflect from the absurd situation. Returning to the basement where the crew was setting up a scene that would make Tony Montana proud, I decided to approach the filmʼs producer/director, Lawrence Page. As a potpourri of firearms lay on the pool table next door, he described to me the history of the video: “I don't see this as a typical rap strand film, Prodigy is not even himself in this film, although he plays a related part. He plays a character from the projects with some others from Infamous Mobb. It's not your typical shootout movie. The films I make always have meaning. Only if you see one or if you watch the way I direct do you understand that I'm telling the truth-I mean anyone can film a guy in the park with a gun in his hand shooting, but is that enough for you to have a story?” I was trying to follow what the filmmaker was saying, but I kept getting distracted by a red dot appearing on his forehead. Glancing behind me, I noticed that one of the boys was playing ʻjoin the dotsʼ with the laser of precision pistols. A shot to the base of my neck woke me up from that induced bubonic stupor and a fragrant haze was pouring out everywhere. One of the crew hit me for the second time as the same loop ran in the background, but was Nas perhaps still singing when the dreams took over?

QUEENSBRIDGE

I was at 41st Street and 21st Avenue in the heart of Queensbridge. The same crew I had met on Long Island was preparing the setting in the projects, and unlike the first time, everyone here knew who Mobb Deep was. While I was idly waiting to do my interview with Prodigy and Havoc a guy from the group asked if I could go buy some food and a few beers. I agreed and went to an Arab grocery store on the corner with a friend who was with me. As the guy at the grocery store was trying to check my age on my papers the disaster began. I donʼt know where it all started but suddenly four 13-year-olds jumped on us threatening to cut us open from head to toe as if for an autopsy. Fortunately, a gentleman intervened, stopping the kids and persuading them to go home. This little episode made me reflect on how harsh reality is in Queens.

Havoc: “I think our music is 100% reality. Even if we are talking about a situation that we haven't exactly experienced on our skin, like killing someone... in those cases we are making rhymes for people who are in a cell for killing someone so that they can really realize that they made a mistake, you know?”

Prodigy: “I think it's a two-part thing. It's entertainment first of all. But for us, in our life, it's not entertainment ... when we walk through that door (pointing to the recording studio door, nda) then it becomes entertainment, spectacle. That's the business part of it.”

Fortunately I returned from the store unharmed, but I no longer felt like waiting a single moment to do the interview. Just as I was making my way to the subway stop the gunfire began. I was scared shitless and, as I had seen done in movies, I started skirting the wall of a building jumping from bush to bush... Were the shots coming from the movie set or from the street? Reality or Fiction? Throwing myself down the steps of the subway, I thought I would not stay to find out.

IN THE LABORATORY

When I opened my eyes again, I found myself in the studio once more. Completely isolated from the outside world, I had no idea what time of day it might be. The only evidence of the passage of time was the previously empty loop of “Scarface,” now occupied by the stanzas of Havoc, Prodigy, and Nas. Just like Pinocchio in Geppettoʼs workshop the beat had begun to pulsate with a life of its own. At that point Prodigy approached me and said he could do the interview, and we sat down with Havoc in the recording room. I thought about everything Iʼd seen, dreamed, fantasized and experienced while waiting to do this interview. I thought about the characters in Havoc and Prodigyʼs ʻfamilyʼ: The Infamous Mobb. I thought of all the nights spent in their company, the smoking, the early morning ʻboxing matchesʼ that I had avoided. But what about their blood families? How do they feel about the careers of their sons Hav and P?

Prodigy: “Well, my father died, my mother likes rap music and she follows what I do. The point is that this is an art form, it's music and she listens to it. Of course she doesn't approve of certain things I say, but she knows they are real things. I think we all know what a mother cannot approve of.”

Havoc: “My mother is happy and my father too. They see this as a positive thing even if they don't like this music, because they realize and know where it comes from. They appreciate it because they know that this has kept me away from prison, crime and these situations.”

Interrupting the interview, a young man from the crew entered the room to inform everyone of his newly graduated degree. And not just from a college, but from Harvard. Shocked, I began to wonder if the diploma he held in his hand was not just a figment of my imagination. A boy born and raised in Queens, a crew representative who at the same time is a student at Harvard...fantastic. To get out of the projects without having to rap, dance, play basketball or get any kind of bad job in the city is really rare. So I decided to ask Hav and P what was the kind of studies they had pursued.

Prodigy: “Hav and I met while attending the College of Art and Design. I went to school to design clothes and he went to school to study architecture. I liked drawing, painting, even t-shirt stuff. Shirt Kings attached this passion to me. As a kid in Queens I was always in the Coliseum at Shirt Kings and that sparked my interest in designing T-shirts.”

Havoc: “I was pretty good at architecture until after I got to the 11th level I started going out all the time and wasting my time doing bullshit, but thank God I only ever did it for music. Music is all I know. Imagine if it didn't exist, life would be over. Besides, I could never work in a McDonald's.”

Although it is good to know that everyone is able to have an opportunity to get a good education, the second interruption we were victims of looked much more like a common ‘Mobb Deep’ situation. A member of the crew (who had been shot that same day during an episode I had better not tell you about) entered the collapsed studio. When Busta Rhymes also joined in, this showed him his wounds in delirium. Havoc's animated response about the violence of which his lyrics are branded kept bouncing around in my head: “What the fuck are you criticizing us for what we write when it's stuff that happens to us every day? Do you want to get rid of us because we tell what happens to us? So they say ‘oh, they're violent, they promote violence...’ We don't promote violence, it's society that's violent! This shit really happens, it happens all the time!”

But was that wound real? How much of what Mobb Deep creates is pure entertainment, like a Schwarzenegger movie, and how much is autobiographical fiction? Arguing about the credibility of Prodigy and Havoc's lyrics is pointless. Whether their lives are then accurately described in their music is a secondary matter. “Murda Muzik” could very well become Mobb Deep's first platinum record, and “Murda Muzik”-the film-will surely cause a small storm. But how will the thousands, millions of kids in the world's suburbs digest an album like “Murda Muzik”? How will they interpret it? Will it only succeed in perpetuating the use of firearms and the philosophy of an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth? How much will Prodigy and Havocʼs own children be exposed to the raw and violent life that is so familiar in their rhymes?

Havoc: “I will let my son listen to whatever he wants, but I will explain to him the difference between right and wrong. I mean if he listens to rap and hears someone say ‘hey, now I'm going to go out and shoot fifty people because I don't give a shit...’ he will already know how to take it because I will have explained the difference. Music is still entertainment, sometimes you put reality into it like we do, but we still never write lyrics about bullshit. Whatever my son hears, he will know the truth.”

JOIN THE PRIORITY LIST

Break boundaries

Break boundaries